Press play to hear the audio version of this post.

After working with Stanley on 2001 I swore I would never work for anybody again, ‘cause Stanley was a hell of a task master. He was difficult, he was demanding, his level of quality control was just astronomically near perfection and I found as a young guy this was very hard. His mind was so insatiable and so active that he could barely sleep - he could barely stop. I saw that Stanley Kubrick worked and lived his work seven days a week, almost twenty-four hours a day, and I think probably he had a hard time keeping up with his own intellect.1

Douglas Trumbull, effects technician, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I imagine you’ve heard the phrase “you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs”. It means that you can’t achieve something worthwhile without making sacrifices. I think that’s all very well, as long as it’s just your eggs you’re breaking. Sometimes the sacrifice is not yours alone, and the phrase comes to mind when considering the incredible career of Stanley Kubrick, one of America’s finest directors.

Many have supported Douglas Trumball’s observation in one way or another, but few people seem to regret working with Kubrick. I’m not surprised: can you imagine having a Kubrick film on your CV? I’d have done the catering to be on those final credits.

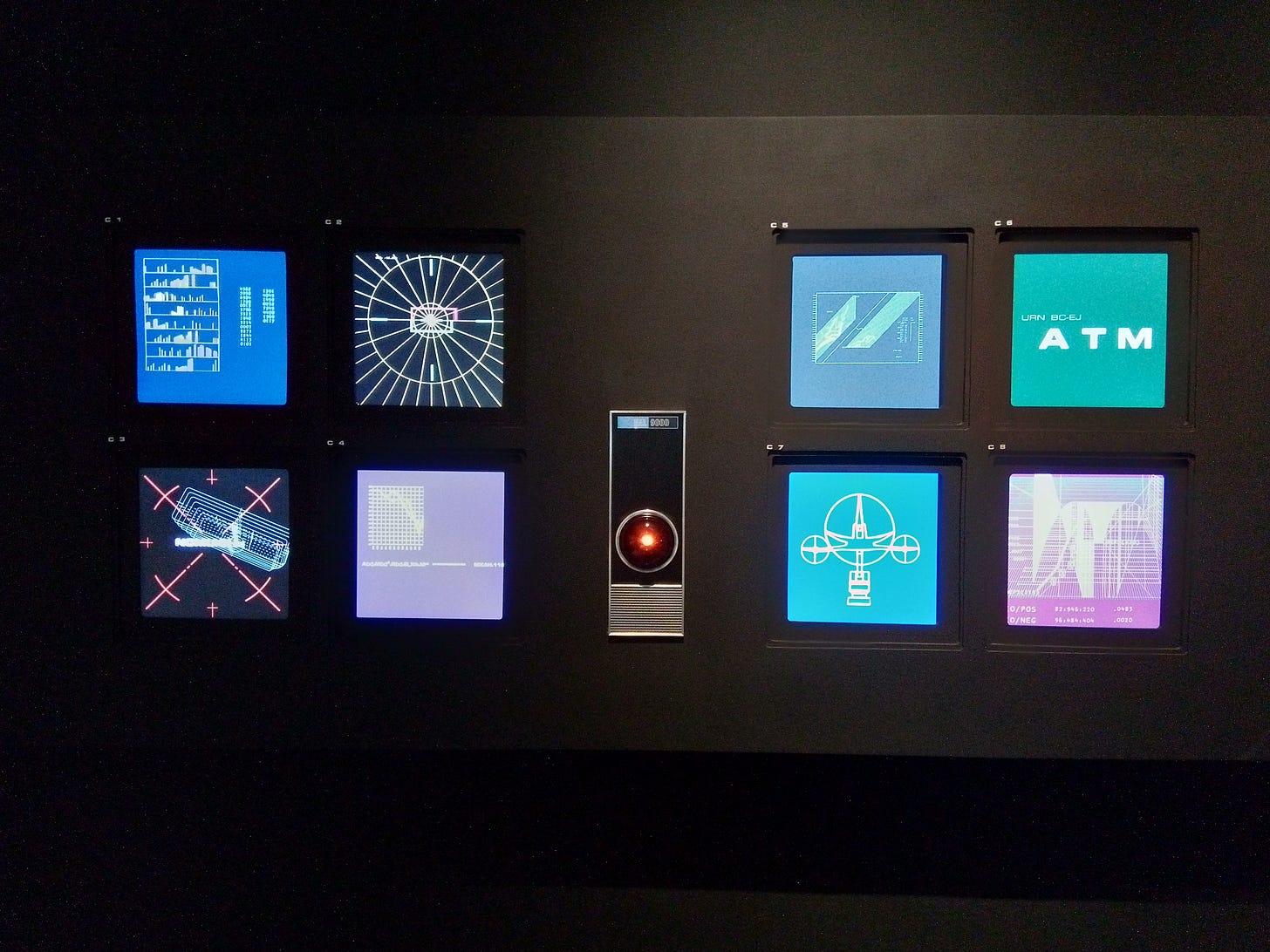

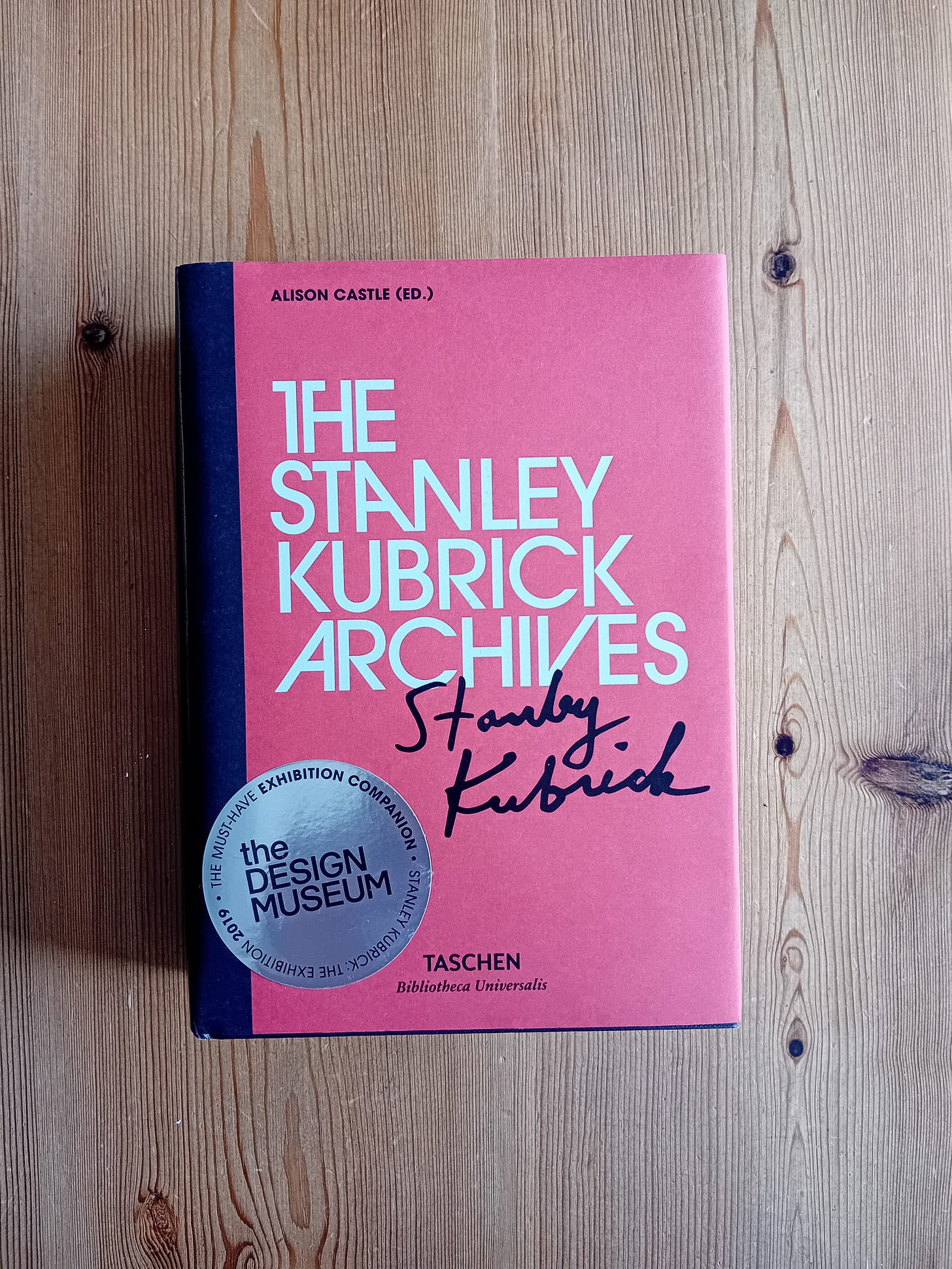

Born in New York in 1928 Stanley Kubrick started his professional life as a photo journalist - he got a job at Look magazine after selling a photo to them when he was only sixteen - and ended it as one of the most highly acclaimed directors of the twentieth century. Over nearly five decades he directed only thirteen major movies, but they gained him huge respect, and in the case of A Clockwork Orange (1971), some notoriety. His obsessive perfectionism is legendary, and when I attended an exhibition called The Stanley Kubrick Archives at London’s Design Museum in 2019 I saw with my own eyes evidence of the enormous trove of equipment and reference material that he amassed over the course of his career.

Regular readers will know that I enjoy an exhibition, and this one was undoubtedly one of the best I’ve ever seen. It was thrilling to stand in front of props and memorabilia from films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), The Shining (1980) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Kubrick’s movies were some of the most eagerly anticipated in the history of American cinema. They were the product of a formidable intellect and tremendous skill as a photographer, screenwriter and director of the highest order. He is responsible for some dazzlingly memorable scenes, the kind that once seen, imprint themselves on your retinas for the rest of your life. Picture, if you can bear it, Gomer Pyle blowing his brains out in Full Metal Jacket (1987), a scene played with excruciating tension by Vincent D’Onofrio, Mathew Modine and R. Lee Ermey. We witness the horror of the final moments of a soldier driven to despair by army training. Even the music used in the scene is nauseating, it’s quiet throb bringing to mind a diseased lung taking it’s final breaths. It’s a savage depiction of the dehumanising effect of military training, and one of its countless catastrophic outcomes.

Who could forget the image of Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance in The Shining, beating down a bathroom door with a hatchet as he screams “Heeere’s Johnny!” at a terrified Shelley Duvall? Another study of a descent into madness.

Luxuriate in the exquisite lighting effects in Barry Lyndon (1975), adapted from a novel by William Makepeace Thackaray, which Kubrick shot using natural light, and in the gaming scene, candlelight. These must be some of the most ravishing images ever captured on film.

Barry Lyndon was set in the eighteenth century, and every costume made for the production was copied from a contemporary painting. Authenticity was such a priority that even instruments used by the Irish marching band were procured from museums. The quest for verisimilitude was seemingly endless, and extended far beyond a propensity for exhaustive research. Marisa Berenson, who played Lady Lyndon in the film, gave an inkling of life on a Kubrick film set:

A lot of it was shot by candle light; a lot of it was shot with…equipment that Stanley Kubrick had found that had never been used before…so it was quite an experience working with that. It was also quite difficult, because there were times when you just couldn’t even move a fraction of an inch, and there were days where we would sit there and just be lit. All day, you know? Literally.2

The French film critic Michel Ciment recorded a series of interviews with Kubrick over a ten year period. Listening to the recordings I was struck by Kubrick’s calm, pleasantly modulated voice, which did not seem to fit the image of a driven genius, a recluse, an obsessive who pushed his actors extremely hard in pursuit of his artistic goals, demanding of them a bewildering number of takes. During the making of The Shining, he allegedly drove Shelley Duvall to breaking point. She addressed the subject with remarkable equanimity, considering what she had been through:

I had never done more than say 15 takes before in my life so it was a great change for me to do so many. But then after you do a certain number it sort of goes dead, and then five more takes or so and it revives itself, and by then you know the scene like the back of your hand, and you can make no mistakes with it, and you forget all reality other than what you’re doing.3

In the documentary made after Kubrick’s death, Jack Nicholson touched on the fact that he and Shelley Duvall were treated differently by Kubrick. Duvall herself spoke of the utterly gruelling shoot and the cruelty that she experienced. She acknowledged that she would not want to go through it again, but also that it had been a fascinating learning experience. There is footage of Kubrick’s very brusque and unsympathetic treatment of her in a documentary made during shooting, and I am convinced by her suggestion that it sometimes seemed as though for him the end justified the means. If you know the film and remember the characters of Jack and Wendy Torrance, Jack’s persona becomes ever more terrifying and domineering as the plot progresses, whilst Wendy’s is perforce ever more petrified and submissive, thus building the tension to an unbearable level. It would seem that Kubrick was prepared to help the process along by encouraging Nicholson to perform in an exaggerated style whilst breaking Duvall emotionally to accentuate her character’s vulnerability: a kind of method acting by proxy. Was Kubrick trying to help her to feel what he wanted her to portray? This is where I reach the limit of my idolatry. If this assessment is anywhere near true, my personal view is that it was several steps too far. On the other hand, Duvall’s performance was exceptional, and I applaud her generosity and wisdom in the way she speaks of her tormentor.

The actor Sterling Hayden suffered a major setback during the making of Doctor Strangelove saying that it was the worst time he ever had on a picture.4 He suggested that it was due to the amount of technical jargon in the dialogue, and nothing to do with the director’s methods. Kubrick told him, presumably by way of reassurance, that the fear in his eyes as he laboured through thirty-eight takes might provide a quality that he wanted. As with Shelley Duvall, this seemed to betray a willingness to push an actor to the limit of their endurance to get what was needed.

It was not only actors who sometimes felt the strain. Composer Leonard Rosenman who worked on Barry Lyndon was pushed beyond the limits of his patience. Of the recording of the soundtrack he said:

We did 105 takes on this thing and take two was perfect.5

Rosenman eventually snapped, threw down his baton and grabbed Kubrick by the neck. He also won an Academy Award.

During the Ciment interviews, Kubrick acknowledged the tension caused by his perfectionism. It is clear that he did not lack empathy - his films prove that - but he would go to great lengths to get the results he wanted. Even Jack Nicholson, an admirer, deemed him “quintessentially perfectionist”, but in an interview he gave after Kubrick’s death he had this to say:

Everybody pretty much acknowledges he’s the man, and I still feel that underrates him.6

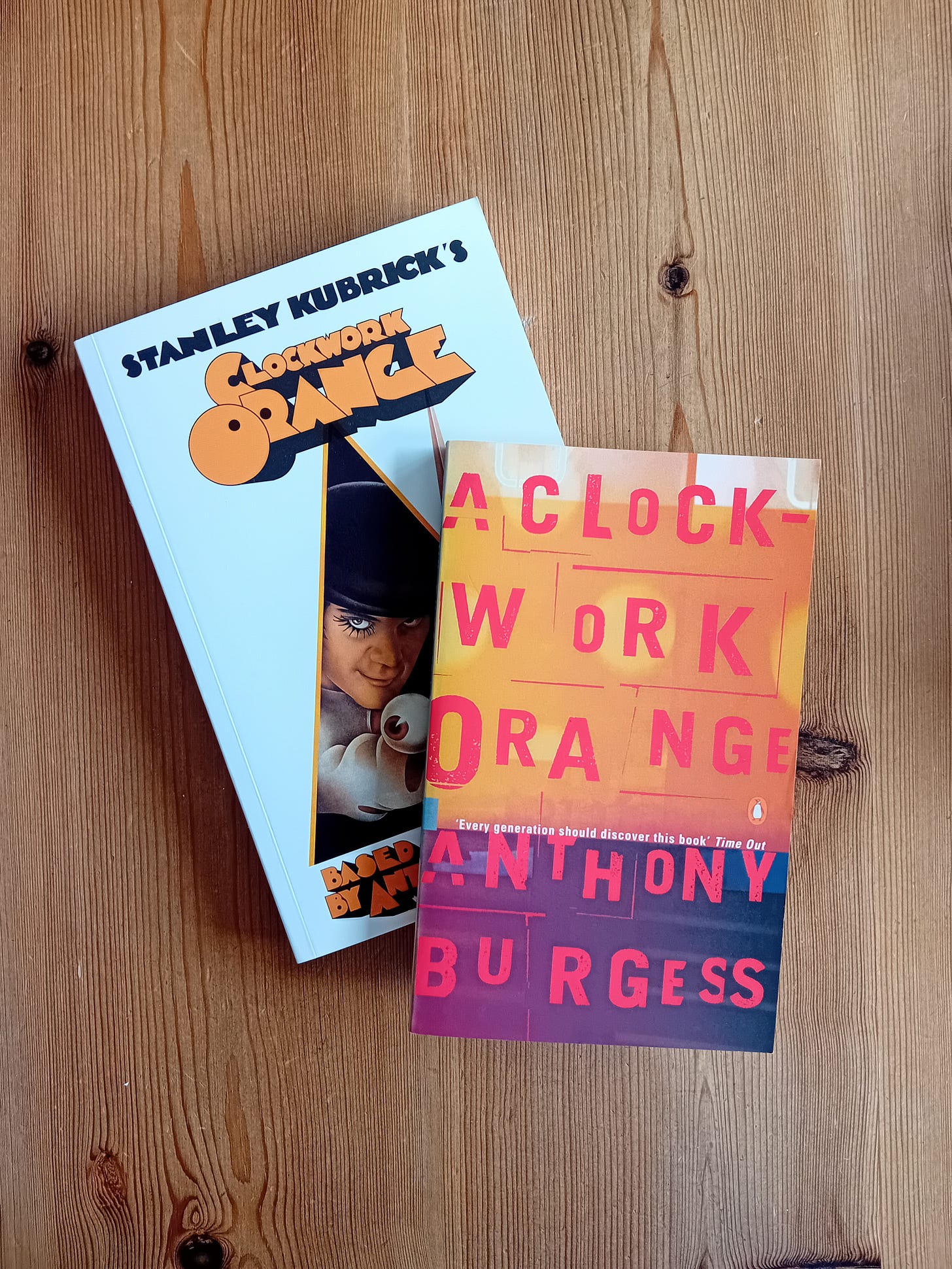

A Clockwork Orange was withdrawn from cinemas in the UK at Kubrick’s behest when it received an alarming public backlash upon its release. It was alleged that it glorified violence. During filming Malcolm McDowell, who played the lead role, suffered injuries to his eyes and ribs as well as a bout of tonsillitis, and unsurprisingly found it a very long and arduous shoot. Like Nicholson, he did not seem to resent these hardships, but offered further valuable insights into Kubrick’s working methods:

This myth going around that Stanley is in complete control…is not true because (he) never knows where to put the camera…he barely knows what scene we’re shooting. He comes in with no preparation, but that’s because he’s an artist you see, and any director who knows what he’s going to do is a very poor director because he must use the…spontaneity that happens on the set.7

When McDowell speaks of a lack of preparedness, he is clearly referring to the creative environment on set. We have already seen how Kubrick’s pre-shoot research was extensive. It would appear however that unlike the director Alfred Hitchcock, who mapped out every scene and camera angle with story boards before a single frame was shot, Kubrick, having made meticulous preparations, allowed filming to develop rather more organically. He claimed that he destroyed thousands of art books whilst researching Barry Lyndon, ripping out countless photographs, likening the process to detective work. Clearly no stone was left unturned during the runup to filming, but once on set, anything was possible.

Kubrick’s movies cover a range of subjects, but they all display an impulse to deal with important moral and philosophical themes. They are films of rare quality, and all the more precious for being relatively few in number. Their scarcity is a testament to the lengthy deliberations involved in choosing and researching a subject, the intensive preparation, and the immense pains taken by the director to perfectly realise his vision. Perfection, if it exists at all, takes time.

I could not argue for the superiority of one of Kubrick’s films over another - nor would I wish to - but my own selections, purely as a matter of taste, would be 2001: A Space Odyssey, Barry Lyndon, The Shining and Dr Strangelove. These four illustrate the diversity of the oeuvre: here we have sci-fi, a period drama, horror and satire. It seems that Kubrick could do justice to whatever subject he chose. Dr Strangelove was probably his most effective anti-war film because the comedy and satire used to address the subject of nuclear Armageddon brought it to the attention of those who might not normally choose war films as desirable viewing. It exposes war for the evil sham that it is, and those who perpetrate it as the buffoons, albeit lethal buffoons, that they undoubtedly are. Peter Sellers, who had already appeared in Lolita, played three roles in it. His performances were brilliant, and it is interesting that an actor with a reputation for being extremely temperamental should have had such an apparently harmonious working relationship with a director such as Kubrick. I adore this line from Dr Strangelove. Sellers as US President Merkin Muffley protests as a fight breaks out between General Buck Turgidson and Soviet Ambassador, DeSadesky, played by George C. Scott and Peter Bull:

Gentlemen! You can’t fight in here! This is the war room!

Kubrick lived in England for nearly forty years. He met his third wife, the artist Christiane Harlan, on the set of Paths of Glory, in which she had a small role. They remained together until his death on 7th March 1999, and raised three daughters. In interview she spoke of him with obvious love and warmth. Family was clearly important to him, and not only did one of their daughters make a brief appearance in 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Christiane’s paintings were to be seen in A Clockwork Orange and Eyes Wide Shut. This was her verdict on the impression of her husband that habitually appeared in the press:

He was not any of the things that the newspapers wrote about him, and he himself said, “It’s very difficult. How do I defend myself? Do I write an article - you know - Dear Public, I’m charming!” 8

Kubrick was an auteur, a recognised giant of cinema, and he created for us some of the greatest films of the twentieth century. He had the respect of Scorsese, Spielberg and Allen. Interviewed for the 2001 documentary, Stanley Kubrick - A Life in Pictures, each of them gave a view on what made him special. I’d be interested to know whether, with the benefit of hindsight, any of the actors and technicians who worked with the great Stanley Kubrick felt that those thirteen wonderful omelettes were not worth a few broken eggs.

Selected Filmography (feature films):

Fear and Desire (1953)

Killer’s Kiss (1955)

The Killing (1956)

Paths of Glory (1957)

Spartacus (1960)

Lolita (1962)

Dr Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Barry Lyndon (1975)

The Shining (1980)

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

What’s your favourite Stanley Kubrick movie?

From the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001).

From the documentary Kubrick by Kubrick (2020).

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

From Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures.

From Kubrick by Kubrick.

Thanks Michael, and for taking the time to respond in such detail.

The thing I find with SK is that his work is always watchable, even if the subject is something you are not sure you will like. When a director is this good there is always a tremendous amount to enjoy.

I agree with you about Eyes Wide Shut. I enjoyed so much about that film, and it was great to see Sydney Pollack in it! The Cruises gave good performances. I think it was a good opportunity for them to transcend their celebrity status at the time and show their acting chops, which I think they did.

I understand SK's early work as a photographer was the bedrock of his cinematic vision. I would love to see more of his photography. To think he sold his first photo to Look magazine at age 16. A prodigy, maybe.

I'm not at all surprised that the world of classical music has to contend with strong personalities. Feelings run deep during the creative process: excellence is demanded, discipline, dedication. Is it worth it? Only the person on the receiving end can decide, I suppose. That's why I so respect Shelley Duvall. She acknowledged how gruelling The Shining was, that SK could be cruel. She also said that it was a tremendous learning experience.

I think he is one of those directors that leave us in no doubt that cinema is a true art. He was exceptional.

Wonderful, wonderful piece. Kubrick is a topic that interests me endlessly. In my opinion, aside from the issue of whether his treatment of colleagues constitutes abuse, he made some artistic errors that I find significant. But even those things don’t keep me from thinking the films in question were great.

Even the Kubrick films where I have mixed feelings are films I can watch over and over. There are many directors for whom I have far greater affection, but that’s about taste rather than objective evaluation. In his best work, his technical virtuosity is in the service of undeniable emotional effects, and it’s hard to argue with that.

I think every great master stands alone, and I tend to find superlatives a dispiriting and wrongheaded approach to artistic evaluation. But when it comes to Kubrick, I can forgive people for using words like “greatest.” His achievement makes it difficult to avoid talking about him that way.