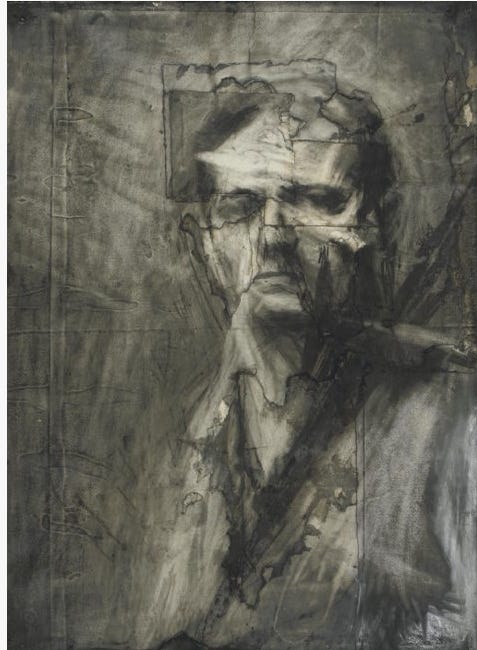

IT WAS immensely encouraging researching this article. Not only has it been a great pleasure to immerse myself in the work of the artist Frank Auerbach, but in reminding myself of his process and techniques, I feel a little less daunted by the idea of not knowing where to start. By the time he passed away last year at the age of ninety-three, Auerbach had produced many works of awe-inspiring beauty which, incidentally, now sell for huge sums, yet even in his final year, as he took up his paintbrush and approached the canvas, he had no idea where to start. Furthermore, he had no idea how to get to the end result, or what that might be.

Frank Helmut Auerbach was born in Berlin in 1931. He was the only child of a Jewish couple, Max, a patent lawyer, and Charlotte, who was from Lithuania. Charlotte had been married before, and had studied art as a young woman. The Auerbachs were comfortably off, but with the rise of Nazism, the situation in Germany became increasingly perilous for Jewish families, and at the age of seven Frank was sent to school in England. On 4th April 1939, he boarded the SS Washington at Hamburg and sailed to Southampton accompanied by three people whom he had never previously met. None of them spoke any English. From Southampton they took a train to London, then onwards to Bunce Court, a progressive school for Jewish child refugees near Faversham in Kent.

Frank would never see his parents again. They were murdered at Auschwitz in 1943. He dealt with this terrible revelation by not thinking about it; by “moving on”, as he put it. Unlike his son Jake,1 he made no attempt to find out more about the fate of his parents, and in old age he retained only fragmentary memories of them. He said that life was too short to brood over the past.

It’s one way of dealing with severe grief and trauma, and it appears, on the surface at least, to have served him well. It is likely that one reason for his robust outlook was the excellent care given to the children at Bunce Court. He felt at home there; liberated. It was more like a family than a school. The headmistress was Anna Essinger, a Jewish, German educator who had been influenced by Quakerism. The school had a free if austere atmosphere, and was staffed by conscientious objectors and refugees who provided a loving environment for the children, some of whom arrived via the Kindertransport. Not all of the pupils were Jewish: the photo editor Bruce Bernard and his journalist brother Jeffrey attended the school between 1936 and 1937.

Frank was extremely happy at Bunce Court. He joined the school theatre group, but it was art that would ultimately allow him to achieve transformation via his creative imagination. Coming across a black and white image of JMW Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire in Arthur Mee’s The Children’s Encyclopaedia was a pivotal moment. Much later he recalled the impact it made on him, describing it as “miraculous art”.

In 1940 Bunce Court was requisitioned by the army, and the school temporarily moved to Trench Hall in Wem, Shropshire. It returned to its original premises after the war, and Frank left in 1947 with his Higher School Certificate and a document of naturalisation. He was sixteen years old.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Dialectic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.