THE FIRST time I saw a Francis Bacon1 painting was probably in London during the late 1980s. I was living in Surrey and I took the train to Vauxhall and walked over Vauxhall Bridge to the Tate Gallery2 at Millbank where I saw a triptych called Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), an image of such searing horror that the amorphous figures seemed to scream their pain at me from the surface of the canvas. They were terrifying, monstrous, and the first time I stood before them they ripped into me with a force that marked my psyche indelibly. It was a shock to my system, one that ensured that I would never forget them or the artist who created them. A fairly typical introduction to the art of Francis Bacon, I should imagine.

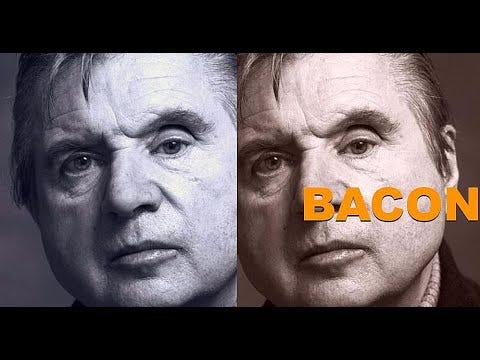

Many years later there was a moment when I realised that Bacon was the real deal. I was watching a documentary when I was struck by the conviction that he really was as good as his status within the art world suggested, and it’s astonishing to think that this man, once considered Britain’s greatest living artist, never had an art lesson in his life.

Aside from its ferocious power, its visceral themes, its challenge, Bacon’s art is a comfort. Despite all its hardships, life is rendered infinitely precious by its limitations. I wouldn’t want to live forever, would you? Imagine the tedium of that. Even so, there are anxieties: will death be painful? Violent? Life is, but that is the attraction of Bacon’s work for me. I have a realistic turn of mind, and avoid the impulse to delude myself in any regard, seeing magical thinking as a threat to survival. Looking at Bacon’s canvases I sense life in all its rawness; I feel a connection that is reassuring, troubling as some of the images are. For all his depictions of the agony of existence, Bacon loved life, and his unabashed view of its realities can be exhilarating. He claimed to be an optimist, but an optimist about nothing. He lived in the moment and emphasised life’s transience: we are born then we die. For decades he spent his leisure time carousing in London’s Soho, mixing with all manner of people, a generous friend to many3. He proved that acknowledging the difficulties of being alive does not preclude one from enjoying one’s time. One of his Soho drinking friends, the Welsh artist Molly Parkin, remembers him fondly in her own memoir, Welcome to Mollywood:

Francis did have a sensitive air and a kindness to him, and there was definitely an aura of fun. He always had a sense that in a moment something totally marvellous was going to happen. He never could give a toss what anybody ever thought about him. He was no respecter of rank.

Parkin describes his dedication to his work, rising at dawn to paint, drinking all afternoon and gambling in the evening. When he won he would share his winnings freely with his friends.

Much as I admire Bacon’s work none of his paintings stand out from the rest as far as I am concerned. I appreciate his oeuvre as a whole since his theme was more or less a constant, an expression of the reality of being alive, being human, the physical, the emotional, the visceral. His imagery is shocking, from screaming popes to monstrous amorphous figures; obsessive, dark, and no doubt influenced by the traumatic times through which he lived. The horrors of war must surely have made their imprint. In more than one interview Bacon described the importance of the subconscious in his work, and perhaps sensations from his early life washed up on the canvas. His father was a severe disciplinarian and violent towards him, and Bacon was allergically asthmatic as a child, living in an environment full of horses and dogs. His sister recalled the asthma attacks that confined him to bed, sweating, white and struggling to breathe. He was influenced by Picasso and the films of Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel, especially Un Chien Andalou (1929), perceiving in them an acute visual imagery of which there is much evidence in his own work. Perhaps the most arresting example of the influence of other artists was Screaming Pope (1953), which resembles an image in Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Velasquez’ portrait of Pope Innocent X, which Bacon esteemed highly.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Dialectic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.